Arshile Gorky

‘I see my life as an artist, as having gone through three main experiences. The first is simplicity, the time of purity. The next is a time of confusion caused from the ordeal of the search for truth. The last is mastering extreme complexity. The last is fruition.’

Arshile Gorky was born in 1904 to Shushanik and Sedrak Adoyan, in a little Armenian village of Khorkom near the city of Van, in the Ottoman Empire. Born as Vosdanig Adoyan, a name he later thought unsuitable. He changed it to Arshile Gorky, which to him sounded more artistic. Besides, gorky is the Russian word for ‘bitter’, a word defining his emotions and state of mind at that period.

In early childhood Gorky’s life was idyllic under the protection of his mother. He was a boy of artistic abilities with an attentive and watchful mind, grasping every detail around him, such as the relief on the wall of the monastery, the miniature illustration in the Gospel of the village church, the butter churn in the kitchen, the pattern on his mother’s apron. The details appeared as shapeless formations and coloured patches much later in his works.

The peaceful family life in Khorkom was interrupted in 1915 during the Armenian Genocide when the severe persecution of Armenians by the Young Turks’ Government in the Ottoman Empire forced Gorky together with his mother and sister to move to Yerevan, where after years of hardship his mother died of starvation in his arms. Gorky was only fifteen.

In 1920 Gorky and his sister arrived in the United States of America. Gorky entered the Rhode Island School of Design. Later he continued his studies at the Grand Central School of Art.

In the eyes of his contemporaries he was a strange foreigner with a funny accent, bold and authentic looks, a strong voice, exemplified by his singing of harmonious Armenian melodies and unconventional dancing. He kept his studio impeccably clean and tidy with all the brushes washed and the pencils always sharpened. This was how he attracted many bohemians and soon was accepted in the group of artists like John Graham, Max Ernst, Breton, Miro, Duchamp and by the critics Harold Rosenberg and Julien Levy. Years later he had his followers in the group; de Kooning, Pollock, Matta and Rothko.

As all great artists, Gorky went through phases. ‘I was with Cezanne for a long time…’ he said once. He was devoted to Ingres and Uccello and finally Picasso. Copying works of these artists matured his colour palette and drawing skills.

After years of hard work, Gorky found his signature style; a symphony of amazing biomorphic shapes. It was a new way of expression. Images were born in the artist’s subconscious, then after being profoundly meditated upon by the artist, they were applied on paper or canvas in oil, ink or crayons.

The ‘archetypes’, as per Carl Jung’s term, images and motifs from the unconscious were emerging into Gorky’s conscious mind. In an amazing drawing and painting technique, masterpieces such as ‘Water of the Flowery Mill’, (1944), ‘How My Mother’s Embroidered Apron Unfolds in My Life’, (1944), ‘The Plough and the Song’ (1947), ‘Agony’ (1947) have been created.

Gorky’s art illuminates light and a limitless sensation of beauty and radiance. His pieces are very sensual and sexual, puzzling the viewer. One can’t just pass by Gorky’s works, as they make the viewer stop and solve the puzzle.

In 1945 Gorky already had his unique style. He was, albeit, unaware that his work was going to start a new movement in American Art; Abstract Expressionism.

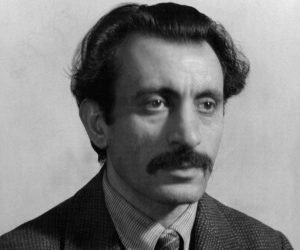

Gorky was tall and handsome. He had an open face with thick dark moustache and deep large sad eyes. He sometimes wore a black velour hat pulled low over the eyes and a black overcoat tight under his chin.

His appearance was dramatic and one of his friends recollected a scene in a museum, when he appeared beneath one of the spotlights. A woman crossed herself, then apologised. ‘For a moment,’ she said, ‘I thought you were Jesus Christ.’ ‘Madam,’ Gorky said, ‘I am Arshile Gorky.’ That was how he confessed his total devotion to art. Speaking as, he thought, he was not less than Jesus Christ in his art. Gorky, indeed, was getting ready to sacrifice himself to Art.

In 1946, twenty-seven of his paintings, all the valuable work of recent years, were destroyed by a fire in his studio in Sherman, Connecticut. Gorky overcame this and started to work with redoubled energy.

However this unfortunate effect had its consequences as his fate continued to fail him: Gorky was diagnosed with cancer. This was followed by a car accident, which paralysed his neck and painting arm. Gorky’s wife Agnes Magruder who was having an affair with Robert Matta, left him taking their two daughters Maro and Natasha.

In 1948, at the age of 44, Gorky hanged himself in their barn in Connecticut. He wrote on the wall ‘Goodbye, my Beloveds.’

Gorky’s works are masterpieces where the intertwined lines and colour patches create the mysticism of abstraction and an enigmatic aura. The artist had reached the most important level of aesthetics where he was able to transfer his emotions from the depth of his soul onto a canvas.

There are no lies or pretence in Gorky’s work. His paintings and drawings are real, sincere and unprotected, like a knobbed pile of naked nerves. Gorky made visible what was invisible through his purity and maturity, as well as his complexity and fruition, through his Art.

Gorky’s work is currently being exhibited as part of Abstract Expressionism at the Royal Academy until January 2nd 2017

by Nouneh Sarkissian